This is the ninth post looking at how ideas from Engelmann’s DI can be applied to the everyday classroom. The first eight can be found here: one, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight

Like the last post, this one will primarily examine The Components of Direct Instruction by Cathy L. Watkins and Timothy A. Slocum, an article from The Journal Of Direct Instruction and an extract from Introduction to Direct Instruction. The paper can be found here:

In the last few posts, I have explored a number of factors that determine whether or not an instructional sequence is effective. Here is a quick recap:

a) We should choose to teach high utility concepts that have wide applications, ensuring that students can ‘exhibit generalised performance to the widest possible range of examples and situations.’

b) Teaching through examples and non-examples may be more efficient than relying upon lengthy, abstract and confusing explanations. Examples should be rigorously chosen and sequenced to maximise clarity and efficacy.

c) Instructional formats should be suited to the level of proficiency of the students. Earlier on, they should be overt and split into logical, sequential steps, allowing teachers to give precise feedback and error diagnosis. Later on, the steps should be removed, encouraging more independent application.

d) Linked heavily to the last point, practice activities and tasks should broadly move along six different continuums as students develop in proficiency.

The Sequencing of Skills

One of the core premises of Direct Instruction is that ‘students should be well prepared for each step of the program to maintain a high rate of success’. On new material, students should be at least 70% successful; on material that is being firmed and practiced, they should be 90% successful. In order to achieve these staggeringly high and impressive success rates, sequences of learning should be systematically ordered according to four main guidelines.

1) Prerequisite skills for a strategy should be taught before the strategy itself.

In a previous post I explored the idea that DI schemes teach ‘everything students will need for later applications’, and this is almost always achieved by teaching the individual, component parts of a more complex skill. The most obvious example of this idea is decoding. If a student cannot decode properly-and it is unfortunate that some still leave primary school in this position-then all other higher order skills are unattainable. You cannot understand the meaning of a text if you cannot convert graphemes into phonemes. You cannot analyse language if you cannot decode it. In fact, if you cannot decode properly, then it is very hard to learn anything at all. Although a few years ago, I would perhaps have accepted that some people will not ever learn to read-ignorance allows the mind to form all kinds of excusatory justifications- I have since learnt that almost everyone can learn to decode, given the right instruction. At our school, we have 6 teachers, including myself, who are trained to deliver Thinking Reading, a systematic and highly effective reading intervention. Our first student graduated from the programme a month or so ago: she began the course decoding at the age of a nine year old, and, after six months, she is now decoding at the age of a fifteen year old, making an average rate of progress of 1 year for every three hours of instruction. If you have students who are weak decoders, then I would highly recommend Thinking Reading!

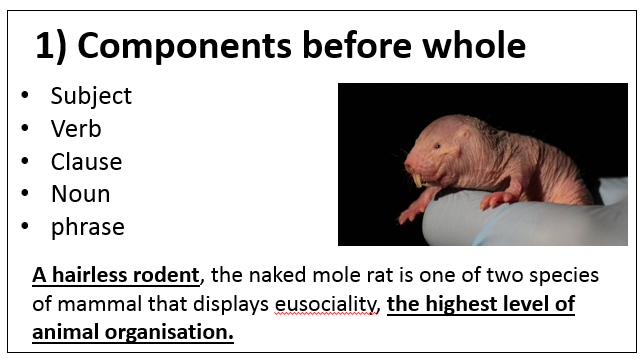

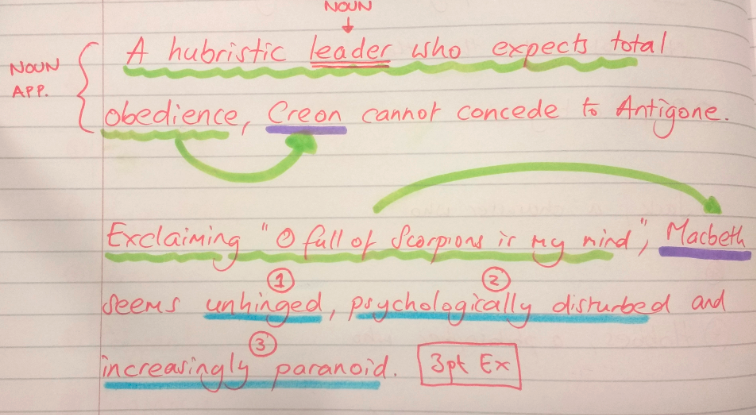

I wrote here about the importance of teaching the different components that make up a complex task before students actually attempt the more difficult application. Here is another example:

The underlined parts of the sentences are noun appositives, constructions that rename nouns within a sentence. The bullet pointed list contains some (not all: you can break this down into far more components!) of the ‘prerequisite skills’ that would need to be taught before students can successfully attempt to create appositives. Kris Boulton wrote a series of blogs about how he applied Engelmann’s ideas to teaching simultaneous equations; this one explores the thirteen sub-components that he decided needed explicitly teaching before students attempted the entire equation.

2) Instances consistent with a strategy should be taught before exceptions to that strategy

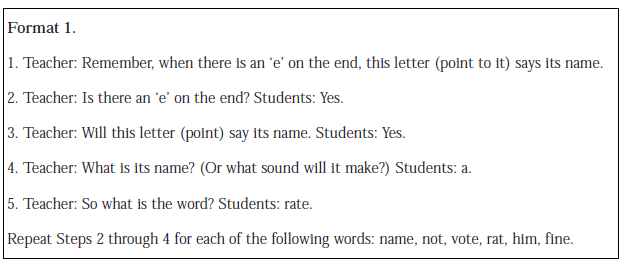

According to the article, ‘Students learn a strategy best when they do not have to deal with exceptions’. When learning something new, exceptions will confuse students and impede their understanding, particularly if the learning is centred around a rule or some form of ‘If-then’ statement. However, ‘once students have mastered the basic strategy, they should be introduced to exceptions. For example, when the VCe rule is first introduced, students apply the rule to many examples (e.g. note) and nonexamples (e.g. not). Only when they are proficient with these kinds of words will they be introduced to exception words (e.g. done)’

Here is an example about eusociality.

Most eusocial species are insects, many of whom belong to the Hymenoptera order. If you were teaching this concept and following Engelmann’s sequencing rule, it may make sense to deal with this large set first, waiting until students have mastered it before introducing mammals and crustacean examples.

Most eusocial species are insects, many of whom belong to the Hymenoptera order. If you were teaching this concept and following Engelmann’s sequencing rule, it may make sense to deal with this large set first, waiting until students have mastered it before introducing mammals and crustacean examples.

In Theory of Instruction, Engelmann presents detailed instructions about how to deal with large sets of items, specifically sets that contain subsets that should be split from the main group and taught separately to avoid confusion.

3) Easy skills should be taught before more difficult ones.

There seems to be a position amongst teachers that allowing students to struggle is a good and desirable thing. Lots of people seem to be talking about Grit at the moment, valorising the idea of resilience in the face of difficulty. Some teachers equate hard work with learning, seeing a strong and fixed line of causation running between them. The problem with this idea is that the success of a program of study is predicated on the tenacity and perseverance of the student instead of the quality of the curriculum or the teacher. While persistence and stoicism are admirable traits that we should praise and encourage, relying upon them for a student’s success seems risky: if the student does not have these characteristics, what then? When I began teaching, I foolishly and ignorantly believed that if I raised the level of challenge, students would magically respond with increased determination and effort, resulting in improved attainment and higher levels of proficiency. Unsurprisingly, this did not work. All I was doing was increasing their feelings of inadequacy and highlighting their lack of understanding whilst doing nothing at all to help them improve. If students begin with easier tasks, they are far more likely to succeed; as the article points out ‘The experience of success is one of the most important bases of motivation in the classroom.’

Here is a possible overview of KS3 poetry teaching, following the ideas that easier skills should be taught first.

Year 7: Teach techniques, sentence level analysis and single paragraph responses.

- Focusing on the sub-components of analysis and getting students to master them in isolation is probably more effective than continually practising the production of multi-paragraph analysis. Not only is feedback easier to give when skills are drilled, but students experience success which is the ultimate form of motivation.

Year 8: Begin to teach comparative structures; multiple paragraph responses.

- Comparing poems is hard: synthesising information from two texts is more complex than dealing with just one. Like in year 7, we begin by drilling comparative structures in isolation, building up to writing comparative multi-paragraph responses.

Year 9: How to approach unseen

- We deliberately leave unseen until year 9 as success here depends heavily upon a student’s vocabulary and background knowledge. Although we teach an approach to unseen in year 9, they still experience the majority of the poems that they encounter through teacher led, explicit instruction. Once students have mastered the approach to unseen, there are diminishing returns to practising lots of unseen poems. Assuming students have mastered the generic approach to unseen poems, if students are attempting multiple unseen tasks without support, what are they learning? Could this time be spent teaching more complex poems and the rich vocabulary that would be needed when responding to them?

GCSE: Consolidation of KS3; analytical essay introductions; development of entire essay responses.

- The idea here is that students enter KS4 having mastered everything that they will need for GCSE, allowing these two years to be used for honing whole essay responses.

Crucially, this progression model is cumulative and all of the easier skills that are taught in the earlier years are encountered, used and applied throughout all subsequent poetry sequences. Students are taught sibilance in year 7 in a unit on Poetry from other Cultures. They will use it again with Romantic poetry, Civil Rights poetry and Dystopian poetry in year 8. In year 9, they will need it when looking at War poetry, Victorian poetry and Shakespearean Sonnets. For GCSE, they will need it again when analysing their anthologies.

4) Keep confusing things separate.

If things are incredibly similar, then we should not introduce them at the same time. I am currently using ‘Teach Your Child to Read in 100 Easy Lessons’ to teach my daughter to read. The ‘d’ sound is taught in lesson 12 and the course waits until lesson 54 to teach the ‘b’ sound because of the huge potential for confusion. Both are voiced consonant sounds and the symbols are exactly the same except for their orientation on the page, reasons why confusion between these two is common amongst weak readers.

Participle phrases and some absolute phrases are very similar and as a result, they should be separated to minimise confusion. As absolute phrases are the furthest away from functional, everyday language, I would probably teach them last, beginning instead with participle phrases.

Present Participle phrase: Raising her voice, she seemed to be getting angry.

Absolute phrase: Her voice raising, she seemed to be getting angry.

Both constructions not only contain participles, but they use exactly the same words, demonstrating just how close these two phrases are to each other.

Whatever subject you teach, there will be numerous examples of pairs or groups of concepts that students confuse, perhaps because of their function, perhaps because of their spelling or maybe because they have similar definitions. If these points of confusion are already apparent, then thinking deliberately about when they are taught and separating them from each other may go some way towards preventing this confusion.

Next post: Cognitive Load Theory-The Worked Example Effect.

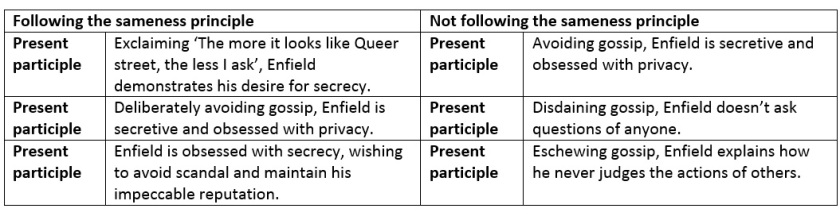

In the left hand column, the non-example is a gerund phrase (the subject of the verb ‘was’). Gerund phrases are often confused with participle phrases and the juxtaposition of these two examples demonstrates why that is: they are incredibly similar. The non-example here is helpful as it gives precise information as to the delineation between ‘present participle’ and ‘not present participle’. In the right hand column, the non-example is massively different, making it harder for a student to ascertain the boundaries of the concept being taught.

In the left hand column, the non-example is a gerund phrase (the subject of the verb ‘was’). Gerund phrases are often confused with participle phrases and the juxtaposition of these two examples demonstrates why that is: they are incredibly similar. The non-example here is helpful as it gives precise information as to the delineation between ‘present participle’ and ‘not present participle’. In the right hand column, the non-example is massively different, making it harder for a student to ascertain the boundaries of the concept being taught.