Analytical Progression Model

- Tentative Language

- 3 Part Explanation

- Zoom In/Technique

- Multiple Interpretations

- Evidence in Explanation

- Link Across Text

When writing analytically, proficient writers substantiate their analysis by referring directly to the text. While indirect references have their place, the use of actual quotations is crucial. When students arrive at secondary school, one of the most important things that they learn in year 7 is how to embed evidence fluently in their writing so that they are equipped to respond to the texts that they encounter. The ability to use embedded evidence is a threshold concept, an idea that once mastered, changes a student’s relationship to the texts that they encounter. Before they cross this threshold, students are able to talk about evidence and textual references; after the threshold has been crossed, this ability is transformed into written output.

Initially, students should be taught to embed single quotations which they can then build arguments around, adding tentative interpretations, zooming in on words and commenting on techniques.

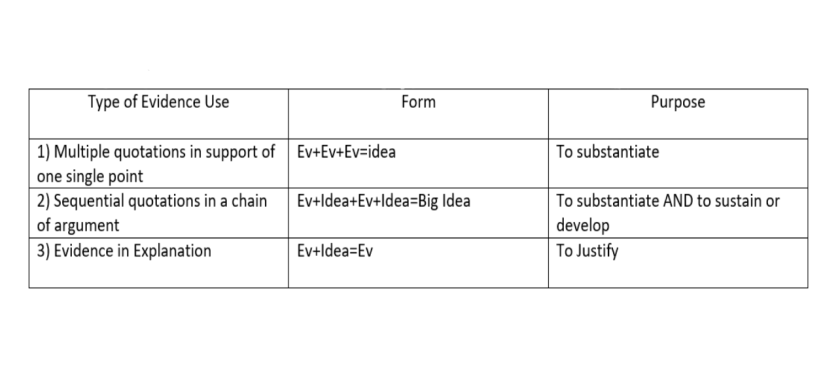

While this is an important start point, more proficient analysis involves multiple pieces of evidence where arguments are sustained and developed through the addition of further textual references. Sometimes this development can take the form of several references in support of one idea; sometimes it can involve a number of sequential references that contribute to and develop a line of argument; alternatively, subsequent pieces of evidence can be judiciously added in order to subtly demonstrate that the ideas within the argument are closely matched to the text itself.

Here are some examples with commentary:

- Multiple bits of evidence that contribute to one point:

Priestley uses dramatic irony to undermine the Birling’s close minded views on the world through phrases such as ‘the Germans don’t want war’ and referring to the titanic as ‘unsinkable.’

In this example, the use of two quotations potentially provides a more substantiated argument. It also demonstrates that the writer is able to notice patterns-in this case both Birling’s habit of pompous pontification as well as Priestley’s frequent usage of dramatic irony. The ability to collate and combine evidence is dependent on two variables: the amount of text that you are using as your evidence base as well as the depth of knowledge that you have of the text. If you set aside the relative complexity of the language contained within a text-Shakespeare is almost always going to be harder than Priestley for students- it is often harder to collate evidence from across an entire text than it is from two sentences, one speech or one page. The former requires a knowledge of far more content. The narrower the source, the easier it is to see patterns; the wider the source, the harder it is to do so.

2) Multiple bits of evidence that sustain an argument-each piece complements the one that precedes it, building an argument and developing a point across a paragraph.

Tempted by the witches prophecy, Macbeth seems torn and conflicted by their words, exclaiming ‘cannot be ill, cannot be good.’ It is as if he desires the throne but recognises that to achieve it, he would need to commit the worst crime imaginable: regicide. When he says ‘whose murder yet is but fantastical’, the word ‘yet’ foreshadows the upcoming crime. Macbeth has very quickly moved from being intrigued by the witches’ language to a position of certainty where Duncan’s murder seems inevitable. Perhaps Shakespeare is exploring the power of greed and how hubris can quickly dominate a character’s judgment.

In this example, the writer is using pieces of evidence sequentially, each building upon the previous and each contributing to one chain of argument or a wider idea. In this case, the writer is analysing Macbeth’s initial reactions to the witches equivocal language and commenting upon the malign influence of hubris.

What to teach?

3) Evidence in explanation:

Birling is an Upper Class man who revels at the idea of ‘lower costs and higher prices’, a selfish notion that conveys Priestley’s argument that the rich exploited the lower classes and treated them as ‘cheap labour.’

He has passed the point of turning back and is in ‘blood stepped in so far’ that his reign causes Scotland to suffer ‘under a hand accursed’

Enfield, like all the upper class men, is singularly focused on his own reputation; he avoids discussion and does not pry into the lives of others because ‘asking a question is like starting a stone’, a statement that conveys his fear of gossip and his desire to avoid ‘disgrace.’

Why Teach it?

In these three models, the final underlined quotation is an example of ‘evidence in explanation’. This approach to using evidence is slightly different as, instead of helping to substantiate or develop and argument, it is being used to justify an argument. When using evidence in this way, the quotation will often come at the end of a line of reasoning, demonstrating that the ideas and interpretations are closely matched to the text itself. If a line of reasoning ends with a quotation-or has one embedded within its final conjecture-then it reads as if the ideas are defensible, lending them a certain credence and making them easier for a reader to accept.

Successful analytical writing treads a narrow line between the need for perceptive and interesting interpretation-essentially the input of the reader-and the need to ensure that these interpretations are based upon textual evidence. If it sways too far from the text, then it can become baseless, absurd or even just plain wrong; if it is swamped with excessive quotations, then analysis and interpretation find no room to breath. A successful essay will achieve this fine balance. It will-to use the language of mark schemes-contain the ‘judicious use of precise references to support interpretation’ and hopefully will avoid the repetitive chaining of PEEL paragraphs where the monotony of the restrictive and clunky structure diminishes the overall quality of the writing. In the absence of a PEEL type structure, students are free to use evidence more flexibly and creatively. While I have touched upon three possible types above, there are undoubtedly many more that could be modelled and practised.

Each category mentioned above is not clear cut and ‘evidence in explanation’ can often be conflated with the sequential use of quotations-this is partly because the process of substantiation is minimally different to justification. While substantiation means to verify through evidence and justify means to explain, in reality the lines between both are blurred. You can explain something by using evidence: a quotation can form an integral part of an explanation. Equally, you can substantiate something by providing further explanation. This ambiguity is one of the reasons why proficient analytical writing can take myriad forms: there are innumerable ways of demonstrating analytical skill and each successful essay will combine a variety of approaches to using evidence. Because of this, helping students to recognise, critique and practice different ways of using evidence can be really helpful in developing their analytical writing.

Next Post: Analytical Introductions-How to ensure students write conceptually.