Here are some explicit instruction approaches for teaching creative writing. All of these are explained in depth in my new book, Explicit English Teaching.

Start with a model text

The ideal model text will have an easily replicable structure that students can emulate or adapt. It will also have certain techniques, components or elements that can be discussed, modified and used by students. Typically, I will spend a lesson or two reading, annotating and discussing a short story that fits this description. Usually, I read the text to give the students a model of good prosody and intonation before asking them to discuss various parts in pairs. If students are asked to find stuff in the text, it is helpful to show them how to do this under the visualiser, pre-empting possible misconceptions or poor selection: only underline the words that you are interested in; your selection should be as concise as possible; make sure you label the type of language (image, word, metaphor etc) as well as making some notes as to what it brings to mind.

Once we have read the story, I will often provide students with a chronological plan that summarises the plot. The short story ‘The Knowers’ by Helen Phillips (in this blog post), has this plot:

Establish idea that you can learn when you will die: dialogue between 2 characters (opposite viewpoints)

Queue for government office to find out: dystopian/bleak

Argument and dialogue between 2 characters: learn day but not year

How to ‘celebrate?’ the day

Description of normal life

As grandparents: learn she will miss birth of grandchild

Final week

Final day

6 minutes to go: still alive

The Knowers is ten or so pages long and students will not be able to produce something of this length in a typical lesson. As a result, it can be useful to show them additional, shorter versions of the story written by the teacher that condense the original while still retaining the structure and the transferable elements. If a model is to be truly useful, it should provide students with flexible, generalisable skills that can be applied to the widest range of relevant contexts. When they write their version, they can use this plot (helping students who struggle for ideas); students who have their own ideas, however, are free to ignore it and use their own narrative structure.

Teach components, initially in isolation

Choosing high utility components (i.e. they have the widest possible application) is an important start point. Asking students to practice anastrophe (how Yoda speaks: jumbled syntax and deliberately incorrect word order) would be a possible example of a low-utility component; asking students to practice combining dialogue with description would be much better as this component will fit lots of creative writing tasks. Components should be taught initially through restrictive drills and practice exercises before asking students to use them in wider writing. This post explores the transition from drills to wider application with regards to analytical writing.

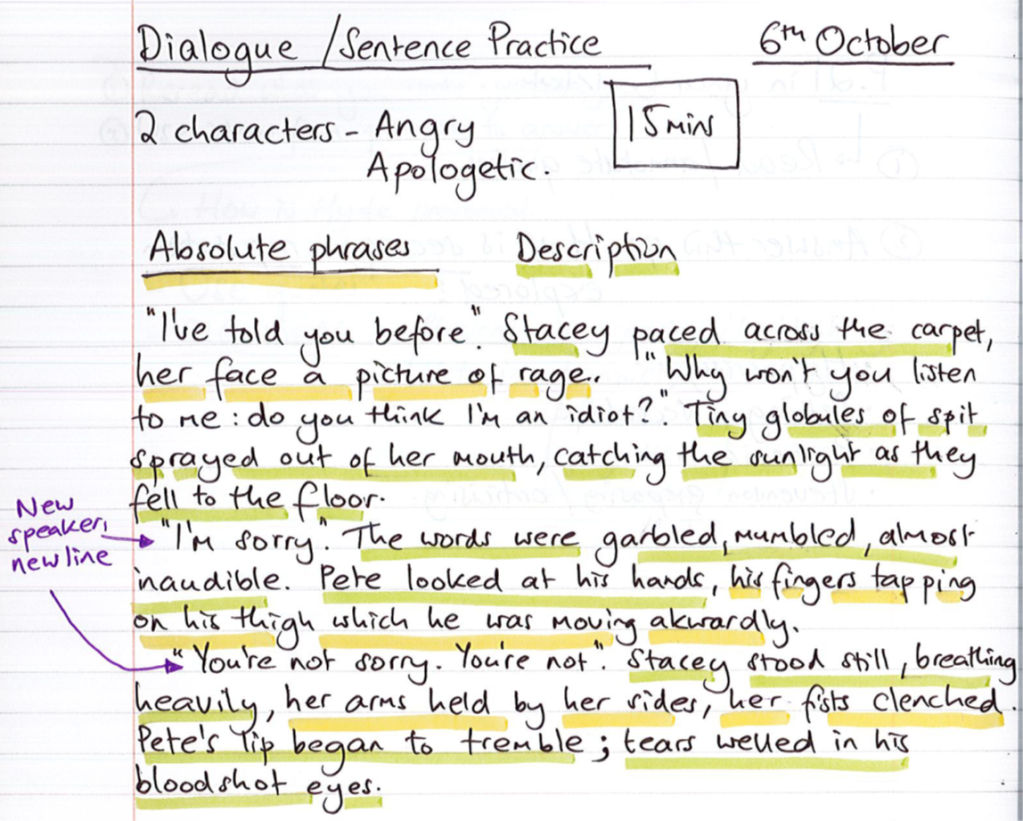

Here are some examples of teaching ‘dialogue with description’:

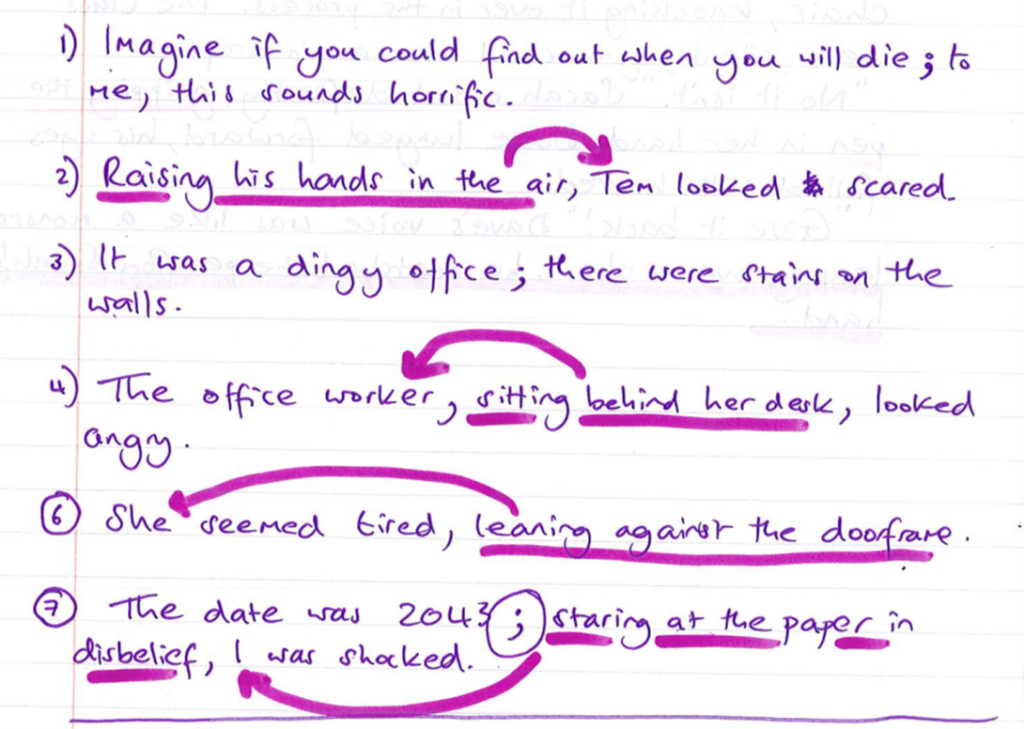

Students in this year 10 class had already been taught to use and manipulate absolute phrases through a 15+ lesson instructional sequence. They had also recapped the conventions of punctuating speech. The exercise above asked them to combine these two skills.

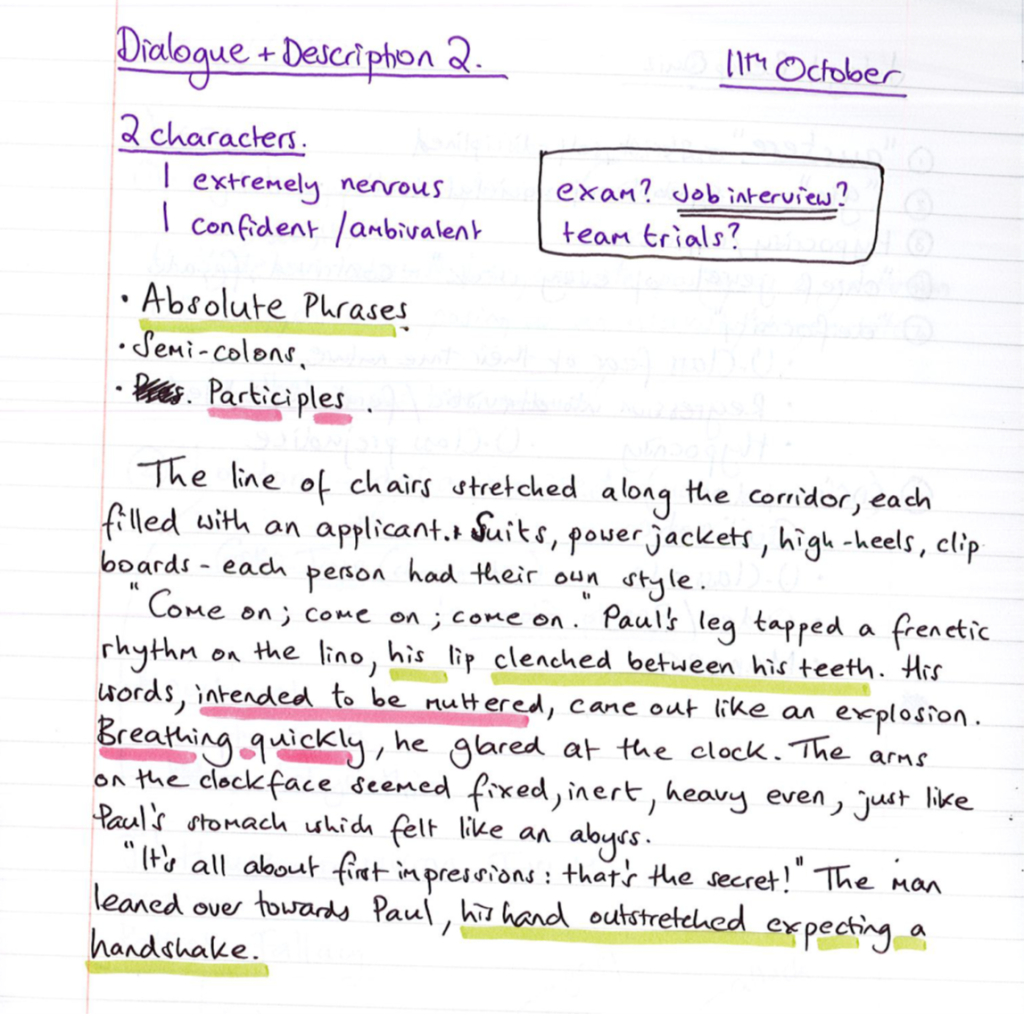

A second activity looked like this:

This second task asked them to combine a wider range of components, each one having been taught initially through isolated practice.

Once students are accurate and fluent in these components (and mini combination drills like the ones above can be really helpful in achieving this), they can be added as success criteria to remind them to include them in their wider writing.

Write while they write

This provides students with further models to borrow from and adapt. The teacher can draw their attention to specific things that they should be trying to include. Here are two half completed versions of The Knowers that I wrote in class:

I have deliberately used the same plot as I want to support the weakest writers, students who are probably more likely to stick to the original plot than create their own from scratch.

Whole Class Feedback to inform next steps

After taking in their books, I will read all their work and make notes as to strengths and weaknesses, the latter being the focus for continuing instruction. This week I asked my year 7 class to write a story inspired by The Knowers and, after having read their work, it was clear that they needed some help with semi-colons and varying their sentence structures. Although they had completed an instructional sequence about semi-colons earlier in the year, many of them are still making errors with this construction. These errors and omissions tell me that I need to look back to the semi-colon sequence as it has not been successful. Does it contain a desirable range of examples? Does the sequence transition from models to completion problems to independent practice too quickly? Is there enough practice? Is there enough later, distributed practice to ensure that students retain this skill?

Whole class feedback, if done properly, should inform curricula change. As Engelmann points out: If they make mistakes, they’re telling you, fundamentally, that you goofed up and they’re also implying exactly what they need to know.’ See this interview for more information.

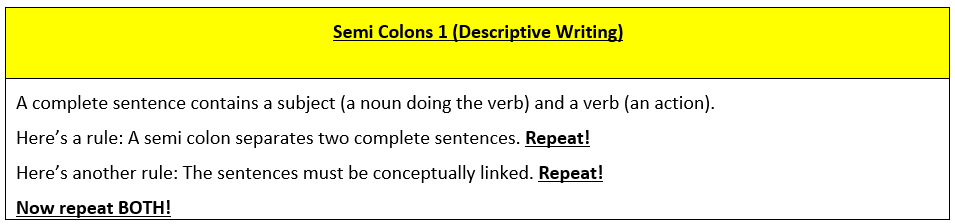

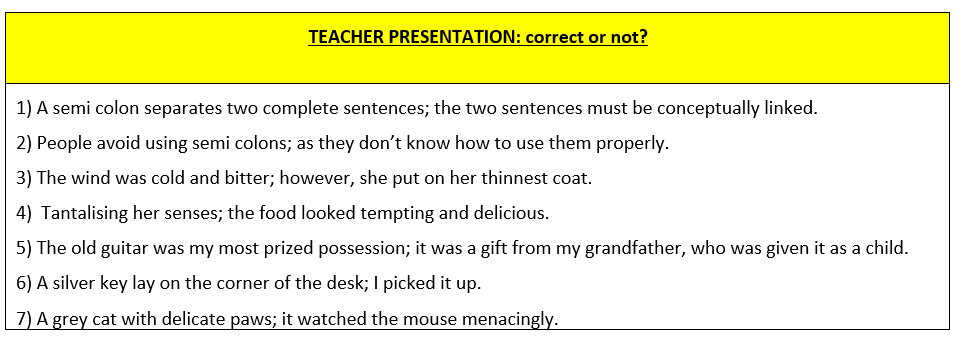

This is what I did to reteach semi-colons:

Task 1: Intro

Because I was fairly certain that the class knew the definition of a sentence, I didn’t need to go back any further to reteach subjects and verbs. If they weren’t secure with these, attempting to teach semi-colons would have been difficult or impossible.

Students chorally repeated the 2 rules and I checked that they understood the meaning of ‘conceptually linked’.

Task 2: Teacher presentation

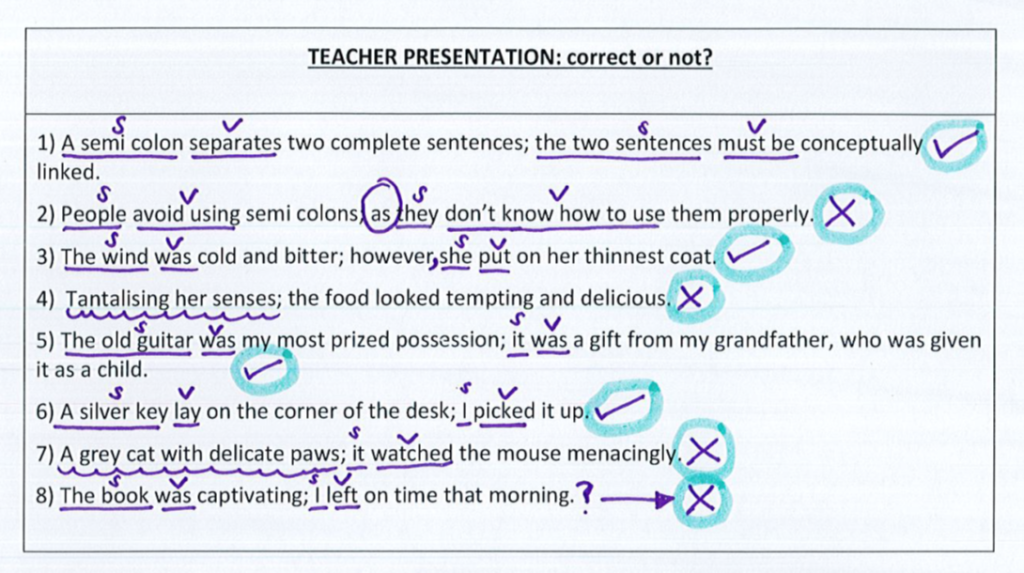

We worked through an instructional sequence that leans on the principles of juxtaposition from Direct Instruction. I read and annotated each of the sentences below in turn. Students did the same on theirs.

By the end of this, students had this on their sheet….

Sentence 8 involved a brief discussion: are the two sentences conceptually linked? Does it make sense? If not, how can we change the second sentence so that it does?

The erroneous sentences contain common errors: using coordinating conjunctions (FANBOYS) with semi-colons; separarting phrases with semi-colons and sentences that are not linked or don’t make sense.

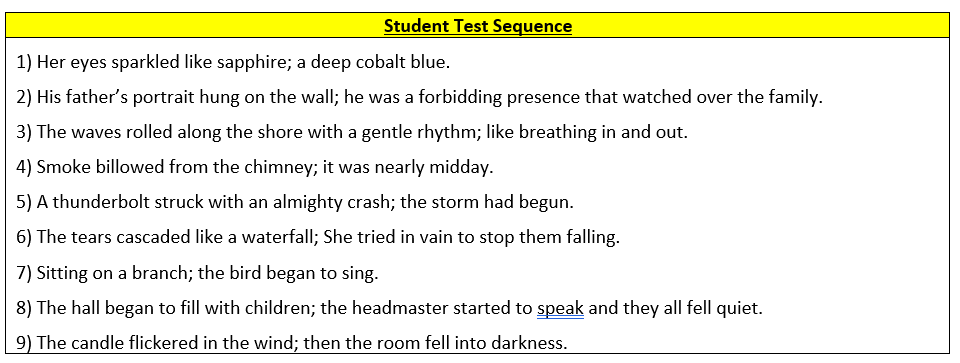

Task 3: Student Test Sequence

Students then had to do the same annotations to a second similar set of constructions, deciding if the sentence is correct or not. This is to check if they have acquired what is being taught as well as whether they can accurately recognise constructions that use semi-colons properly.

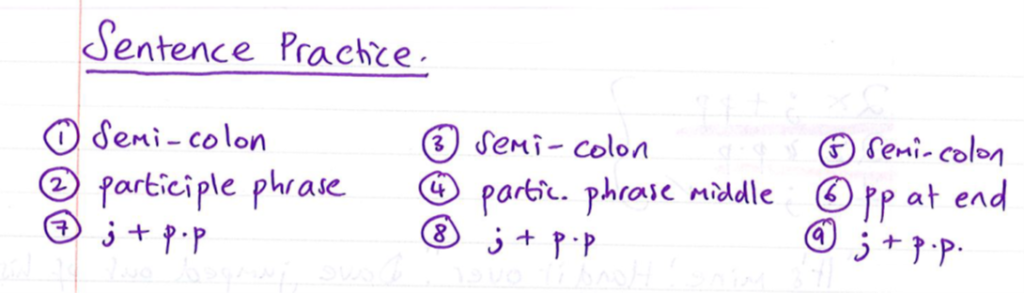

Task 4: Independent Practice

Because the student success rate was really high, I then asked them to begin some independent practice and produce sentences of their own.

This task initially asks them to produce semi-colon or participle phrase sentences before asking them to combine these two constructions together to form more complex sentences. They wrote sentences based upon their version of The Knowers. I quickly wrote some on the board to give some further examples. While they were writing, I went round and checked all students giving hints and prompts to ensure they were being accurate.

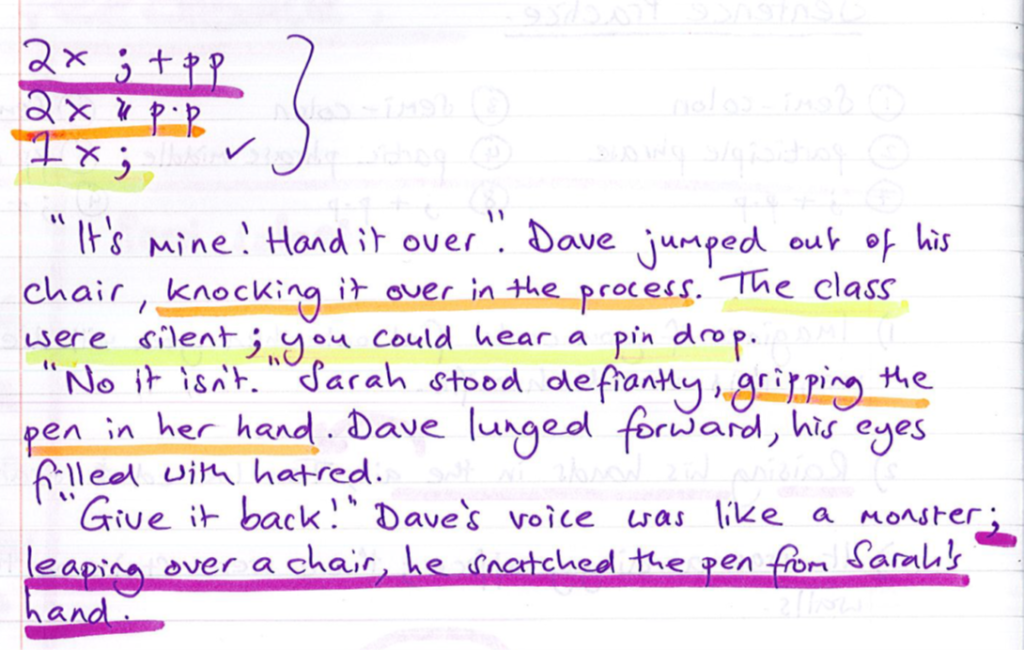

Task 5: Wider Independent Practice/Integration with other skills

After checking all books while they were writing to ensure that success rates were high enough, I then asked them to combine these sentences with ‘dialogue and description’, the high utility component that I explained earlier in this post. Students were asked to describe an argument between two people and had to use the constructions from the previous tasks in this short piece of creative writing. While they wrote, I wrote mine under the camera, labelling where I had used the constructions and providing further support for those who needed it.

What is next for this year 7 class?

- More varied and distributed practice that asks students to combine all of these skills across a number of lessons.

- Teaching additional high utility components, initially in isolation before being gradually integrated with these.