This is the eighth post looking at how ideas from Engelmann’s DI can be applied to the everyday classroom. The first seven can be found here: one, two, three, four, five, six, seven.

Like the last post, this one will primarily examine The Components of Direct Instruction by Cathy L. Watkins and Timothy A. Slocum, an article from The Journal Of Direct Instruction and an extract from Introduction to Direct Instruction. The paper can be found here.

The 6 ‘shifts’ of task design

The last post looked at idea that ‘the support that is so important during initial instruction must be gradually reduced until students are using the skill independently, with no teacher assistance.’ According to the article, ‘Becker and Carnine (1980) described six ‘shifts’ that should occur in any well-designed teaching program to facilitate this transition’.

1) The shift from ‘overtised’ to ‘covertised’ problem-solving strategies.

Initial instruction will break down a concept or strategy into multiple individual steps (see ‘Format 1’ in this post). In Theory of Instruction, Engelmann explains the difference between physical and cognitive operations. A physical operation includes things like ‘fitting jigsaw puzzles together, throwing a ball, ‘nesting’ cups together, swimming, buttoning a coat’-essentially any process that involves a series of steps that may include motion or the manipulation of matter, and one that receives immediate ‘feedback’ from the environment. If you are trying to hammer a nail and not doing it properly, the environment will give you ‘feedback’ and prevent you from completing the physical operation. Perhaps you missed the nail. Perhaps you didn’t use a hammer. Maybe you didn’t hit the nail hard enough. Perhaps you used the wrong striking technique. The important idea is that it is easy for an instructor to observe the reason behind your failure because the entire process is overt and each step is observable. For cognitive operations, ‘there are no necessary overt behaviors to account for the outcome that is achieved’. Essentially, we do not know how an outcome has been reached unless all the individual steps are made overt. A student may have got lucky; they may have relied upon a rule that, while being effective in this instance, may end up causing problems as a sequence become more complex. Unlike with physical operations like hitting a nail with a hammer, the physical environment does not provide feedback for cognitive operations. This passage from Theory of Instruction explains this idea further:

‘The physical environment does not provide feedback when the learner is engaged in cognitive operations. If the learner misreads a word, the physical environment does nothing. It does not prevent the learner from saying the wrong word. It does not produce an unpleasant consequence. The learner could look at the word form and call it ‘Yesterday’ without receiving any response from the physical environment. The basic properties of cognitive operations-from long division to inferential reading-suggest both that the naïve learner cannot consistently benefit from unguided practice or from unguided discovery of cognitive operations. Unless the learner is provided with some logical basis for figuring out possible inconsistencies (which is usually not available to the naïve learner), practicing the skills without human feedback is likely to promote mistakes.’

Making the steps of a cognitive operation overt allows extremely precise feedback to be given as the instructor can easily see the reason behind a particular outcome. During the acquisition phase of learning-the initial stage where, in the absence of teacher support, a student would soon become confused-precise and immediate feedback is of crucial importance, preventing errors from becoming embedded and ensuring accuracy is achieved. If students engage in ‘unguided practice or…unguided discovery’ then they will flounder; this is the central idea behind the influential Kirschner, Sweller and Clark paper which critiques one of the popular premises behind progressive education.

How does this apply to English?

1) In this post, I demonstrated an initial (flawed) communication sequence for teaching students to select and punctuate quotations, exemplifying how the covert can be made overt.

2) Precise feedback is vital: try making restrictive practice activities that isolate and focus on the specific content that is being taught: this post explains one way of doing these.

3) When students write sentences, ask them to feedback orally by saying/narrating the punctuation, turning the covert into the overt and allowing you to quickly and efficiently ascertain if they have succeeded without having to actually mark or look at their book. If appropriate, other students can listen and give feedback about accuracy too!

EXAMPLE:

Teacher: Read out your absolute phrase sentence, narrating the punctuation

Student: His paranoia growing COMMA Macbeth seems increasingly unstable and unhinged FULL STOP.

4) Live modelling: creating example sentences, paragraphs or even essays under the visualiser whilst narrating your thought process is a really powerful way of letting students observe the process of writing. When this process is made interactive with lots of teacher-student questioning, it can be even more effective.

2) The shift from simplified contexts to complex contexts.

In sport as much as in teaching, drills deliberately isolate elements to practice, increasing the amount of practice and decreasing cognitive load. Drills allow students to focus on ‘critical new learning’.

In Expressive Writing 2, one of the DI corrective writing schemes, one of the key skills that is taught is punctuating direct speech. Here is an overview of the ‘track’ (series of lessons) where this skill is taught and applied: this track spans 48 lessons! (See this post which explains the idea of a strand curriculum where multiple ‘tracks’ are intertwined over time).

1) Lesson 2,3,4: The rules for punctuating direct speech are introduced. Students are heavily directed by teachers and, following detailed and precise modelling of examples, have to complete isolated sentences of punctuated speech.

2) Lessons 5 to 9: Students write their own simple sentences that contain direct speech with minimal prompts. Sometimes they are statements; sometimes they are questions.

3) Lesson 10,11,12: Students edit and correct individual sentences that contain direct speech, adding in missing punctuation marks and capital letters.

4) Lesson 13 and 14: Students edit sentences in a paragraph that includes direct speech, adding in missing punctuation marks and capital letters.

5) Lesson 16 and 17: Students punctuate direct speech that includes two consecutive sentences.

6) Lesson 18: Students edit and correct an entire passage with two-sentence direct speech.

7) Lesson 24 to 28: Students punctuate direct speech that appears at the start of a sentence.

8) Lesson 33 to 37: Students punctuate sentences that include two different pieces of direct speech that are separated.

The practice activities gradually build in complexity in two ways: firstly, the subject matter and what is being taught slowly becomes more challenging; secondly, the context of the practice changes from isolated, supported drills to increasingly complex and contextualised activities. As the scheme progresses, students are increasingly asked to apply these component skills within a freer piece of writing, something that almost all of the lessons end with.

How does this apply to English?

Following this ‘shift’, I wrote here about how skills and items that are taught can be moved from simplified to more complex contexts.

3) The shift from prompted to unprompted formats

According to the article, ‘In the early stages of instruction, formats include prompts to help focus students’ attention on important aspects of the item and to increase their success. These prompts are later systematically removed as students gain a skill. By the end of the instruction, students apply the skill without any prompts.’

How does this apply to English?

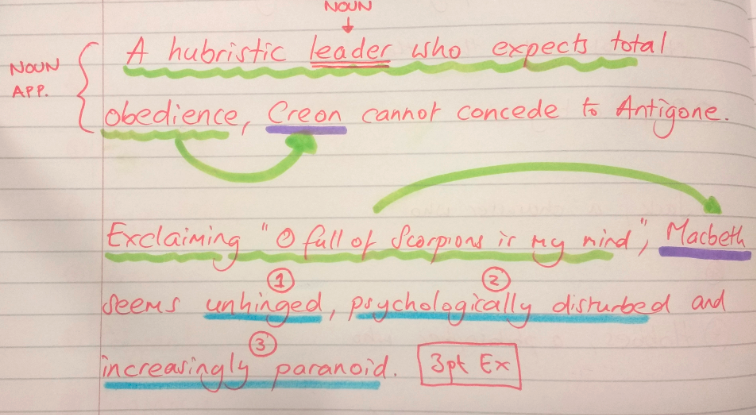

1) In the earlier stages of instruction, worked examples should be labelled clearly, identifying relevant bits and making clear to students which parts are important.

Here is an example:

2) When teaching sentence styles, arrows and labelling can help make the implicit interactions and relationships between different components obvious to students.

Here is an example:

4) The shift from massed practice to distributed practice

According to the article ‘Initially, students learn a new skill best when they have many practice opportunities in a short period of time. In later learning, retention is enhanced by practice opportunities conducted over a long period of time.’ During the acquisition stage of learning, it may be helpful to have multiple practice opportunities in order for students to become proficient with a concept. As the sequence progresses, this practice should become increasingly more distributed.

How does this apply to English?

1) This post looks at an example lesson plan, exemplifying how concepts are initially taught via massed practice and then move to distributed practice, through regular and systematic retrieval practice.

2) This post looks at the journey of a test item across multiple lesson, again moving from massed to distributed practice.

5) The shift from immediate feedback to delayed feedback

At the beginning of an instructional sequence, feedback should be immediate and precise, preventing errors from becoming embedded. Although feedback is lauded as a universally positive thing-the implication being that the more you give, the better students will perform and learn-this notion is overly simplistic and erroneous. The EEF point out that ‘Feedback studies tend to show very high effects on learning. However, it also has a very high range of effects and some studies show that feedback can have negative effects and make things worse.’ Referencing Soderstrom and Bjork’s ‘Learning versus performance’ paper (accessible here), David Didau points out that ‘there is empirical evidence that “delaying, reducing, and summarizing feedback can be better for long-term learning than providing immediate, trial-by-trial feedback.” This last point seems to corroborate Engelmann’s idea that the optimum type of feedback will change according to the stage of instruction.

How does this apply to English?

1) Initial practice activities of all concepts (analytical skill, vocabulary, context knowledge, sentence styles, punctuation etc) should be through restrictive and isolated drills, allowing precise and immediate feedback to be given. A teacher can either circulate, giving verbal feedback, or write a model and, by displaying it under the visualiser, provide students with an answer with which to check their own efforts against.

2) Regular cumulative recap quizzes at the start of lessons provide the perfect opportunity for immediate feedback regarding spelling and conceptual understanding. Referring to the ‘hypercorrection effect’, the idea that ‘The more confident someone is that an incorrect answer is correct, the more likely they are not to repeat the error if they are corrected’, Dylan Wiliam explains that ‘The benefits of testing come from the retrieval practice that students get when they take the test, and the hypercorrection effect when they find out answers they thought were correct were in fact incorrect. In other words, the best person to mark a test is the person who just took it.’ Following this advice, we conduct retrieval practice under the visualiser, filling in the answers immediately after the quiz, and asking students to check and correct their own work.

6) The shift from an emphasis on the teacher’s role as a source of information to an emphasis on the learner’s role as a source of information

This shift matches the idea of ‘I-we-you’, where responsibility and agency gradually moves from teacher to student. This table from p.72 of Teach Like a Champion, illustrates this shift:

How does this apply to English?

Let’s take an example from writing paragraphs:

1) The teacher writes a paragraph under the visualiser, narrating thought process and decisions (The ‘I’ stage)

Using a semantic field of light, Dickens describes Scrooge’s room with words like ‘bright…gleaming…glistened’, symbolising warmth, comfort and opulence. Perhaps the ghost wants Scrooge to experience a convivial and celebratory scene so that Scrooge will not only realise that being as ‘solitary as an oyster’ is a bad choice, but that he could spend his money and enjoy himself instead.

- If students have been already acquired the analytical skills, you could ask them to identify them (3 part explanation/evidence in explanation/tentative language/multiple interpretations)

- Quick fire questioning about vocabulary (convivial/opulence/semantic field will provide valuable retrieval practice.

2) Teacher begins a second paragraph under the visualiser, asking students to help them complete it. (The ‘We’ stage)

Using a hyperbolic metaphor, Dickens describes the food as ‘…..

- If you use the same structure as the first paragraph, students have a framework to follow (taking advantage of the alternation effect from Cognitive Load theory)

- The teacher can prompt students to use taught vocabulary or specific sentence styles

- When complete, you could undertake another round of quick fire questioning, again providing valuable retrieval practice.

3) Students now have 2 models to use as analogies. They should then write their own paragraph using different evidence but following the same process and structure. (The ‘You’ Stage)

Next post: Insights from DI part 9-The Sequencing of Skills. What principles should guide how we order instruction?