This is the fourth post looking at the application of Cognitive Load Theory to teaching English. The first three posts can be found here: one, two, three.

Teaching students how to write is an essential part of not just teaching English, but also teaching other subjects too. Over the last few weeks, an excellent series of blogs has been written by science teachers exploring the importance of written expression in their subject and these posts are worth a read whatever your subject specialism. Like them, my teaching has also been heavily influenced by The Writing Revolution, a book that explains the importance of explicitly teaching students to practice and apply specific sentence structures to their writing, thereby developing not only their range of expression, but also the precision and sophistication of their written output. When teaching writing explicitly, both at sentence and paragraph level, the use of worked examples and backwards fading can help students achieve a high success rate as well as ensuring that learning is as efficient as possible.

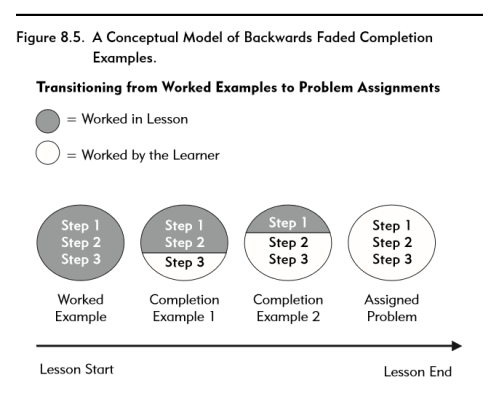

Here is a conceptual model of this process from Efficiency in Learning by Clark et al:

This post will explore the application of Cognitive Load Theory and specifically backwards fading to the teaching of noun appositives.

One of the sentence constructions explained in The Writing Revolution, noun appositives allow students to add extra detail into their writing. This blog post explains their form and usage in more detail.

Although I would have begun the teaching of appositives with multiple lessons that contain sequences of examples and non-examples, allowing students to see the range and limitation of the construction as well as anticipating any common misconceptions, what follows demonstrates the application of the worked example effect and backwards fading to an instructional sequence.

Lesson 1 Step one: Present and label examples

- A poem that denounces exploitation, London conveys the omnipresence of suffering.

- Ozymandias, a poem that highlights the transience of human power, demonstrates that nobody is immortal.

- A callous capitalist who disdains collective responsibility, Mr.Birling is only concerned with ‘lower costs and higher prices’

Depending on the class, this may be entirely teacher led or may involve a series of questions asking students to help with labeling: What is the subject of the sentence? Where is the verb? What is London? It is a poem that denounces exploitation. What is Ozymandias? It is a poem that demonstrates the transience of human power.

As mentioned in this post, using arrows, prompts and labeling can help make the implicit interactions and relationships between different components obvious to students.

Lesson 1 Step two: Begin further examples and ask students to orally complete them

Teacher writes this under the visualizer:

- A manipulative woman who berates her husband,

The teacher can then ask a number of retrieval practice questions like Who does this describe? What does manipulative mean? What does berate mean? Why does she do this? With a weaker class, the teacher may want to give several completed oral examples before asking students to attempt their own. Students can then complete the sentence orally, a task that allows students to experience success before even attempting to write their own answers. Stronger students can offer ideas first, allowing weaker students to hear further examples before attempting it themselves. Asking students to narrate the punctuation in their spoken sentence (A manipulative woman who berates her husband COMMA Lady Macbeth…) helps to draw attention to the necessity of punctuation in the construction.

To further focus the practice or raise the level of challenge, the teacher can ask students to include specific things in their completed oral sentences.

Example:

- A manipulative woman who berates her husband,

Include:

- ‘pour my spirits in thine ear’

- sinister

Lesson 1 Step three: Begin further examples and ask students to complete them in writing

Students are presented with a series of half completed examples and are asked to complete them. With weaker classes, it may be useful to complete an example or two under the visualizer, narrating your thought process so that students know exactly what they are supposed to do.

- A tyrannical and vainglorious King, Ozymandias

- Hyde, a sadistic character who…………………………………………………., seems

- A criticism of……………………………….., An Inspector calls encourages the audience to

- The archetypal Victorian gentleman, Utterson

Because of the restricted nature of these completion problems, precise and immediate feedback can be given by the teacher. Students can be asked to read out their sentence, again narrating the punctuation so that the teacher-or students for that matter-can ascertain whether it is correct or not. This is a much faster feedback loop than taking all the books in and marking them. The teacher can then ask further questions to the student who gave the sentence (or different students) about the completed construction in order to draw attention to the function of the appositive or to provide further retrieval practice about the content of the sentence.

Example:

Student: The archetypal Victorian gentleman COMMA Utterson is ‘austere’ and secretive COMMA avoiding fun at all costs.

Possible Teacher questions: Read out just the appositive. Who does it rename? What does archetypal mean? Which word in the sentence is a quotation? What does ‘austere’ mean? What specific things does Utterson do that make him ‘austere’? Is he always like this? Why is his secrecy a form of duality?

If the sentence contains a weak point, the teacher-or other students-can make suggestions for improvement:

What is a better word for ‘fun’? Frivolity. Crucially, all students are able to answer this as the question is asking them to apply vocabulary that has been explicitly taught in previous lessons.

Like with the oral completion exercises, the level of challenge can be raised by asking students to include specific things in their answers, helping them to make links between different bits of knowledge.

Example:

- The archetypal Victorian gentleman, Utterson

Include:

- ‘repressed’

- ‘never lighted with a smile’

- contrived socializing with Enfield

In Expressive Writing 2, a Direct Instruction writing scheme, most lessons end with a single or multi-paragraph piece of writing and students are asked to complete a series of precise checks when they have completed their writing in order to ensure that they have applied a necessary skill and avoided making common, careless errors. This approach is also useful to the everyday classroom: instead of asking students to check their work-a vague statement that may be interpreted by students as ‘skim read a bit of it’, it can be useful to specify exactly what they are checking for. These common errors can either be based upon what is being taught (the most likely mistakes that students will make when attempting the task) or they can be based upon the class that you teach, having been chosen as a result of feedback to the teacher: if a weaker class are, on average, bad at using full stops, then include that as a check. Like in Expressive Writing, I would ask students to complete one check at a time in order to prevent cognitive overload.

Possible example checks for appositives:

CHECK 1: Does your appositive rename a noun that is right beside it?

CHECK 2: Is your appositive separated from the rest of the sentence with a comma or pair of commas?

CHECK3: Does your sentence end with a full stop? (This check would be unnecessary for more proficient students!)

You may have noticed that I have still not asked students to complete problems on their own and this is deliberate. I want students to experience quick, initial success with writing these structures and spending time and effort on worked examples and completion problems allows this to happen. By doing so, students-even weaker ones-can experience high initial levels of success, something that both Engelmann and Rosenshine have identified is of crucial importance in instructional sequences. If students are successful, this raises their motivation levels: even the most apathetic students can become enthused if it is clear that they can succeed.

One lesson is not enough however, and instruction should continue in a track system across multiple lessons so that students develop automaticity. The instructional sequence should aim to broadly follow the idea of backwards fading, slowly removing prompts and scaffolding so that students eventually apply their knowledge independently and without support. Finally, tasks should slowly change from isolated and decontextualized sentence practice to wider application within paragraphs and extended writing.

Here is a rough overview of what might happen in subsequent lessons:

Lesson 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6: Further worked examples and completion problems

Although the first lesson that I described would probably be a dedicated ‘Appositives’ lesson, the subsequent lessons would more likely be practice tasks within lessons that contain many other foci.

While earlier lessons saw the teacher leading the labeling and annotation of the worked examples, as students become more proficient, they can be asked to do this themselves. The completion problems would be less restrictive, giving the students more autonomy and requiring them to complete more of the steps themselves. While the earlier completion problems provided the noun that does the renaming (A vainglorious and tyrannical king, Ozymandias…) the examples below require students to generate it for themselves:

Examples:

- Hyde, a…………………………………………………………, is the opposite to

- A…………………………………………………………, Lady Macbeth

- A……………………………………………………………, The Prelude

Lesson 7, 8 and 9: Interleaved Completion Problems

These lessons may ask students to complete a range of different sentence styles, interleaving appositive practice with other constructions. In the example below, semi-colon practice is mixed up with appositive practice. Like with the appositives, students would have already completed the ‘I and We’ stages with semi-colons before encountering them in this interleaved exercise.

Example:

- A denunciation of…………………………………………….., London……

- The Inspector admonishes the Birlings for their callousness; he wants

- Macbeth’s sword ‘smoked with bloody execution’, an image that demonstrates….

- Lady Macbeth, a manipulative……………………………………………, berates…….

- Duncan is oblivious to their plans; he…..

Lesson 10, 11 and 12: Independent Problems.

At some point, the worked examples become unnecessary and redundant as students will have developed a mental conception of what it is that is being taught. Instead of studying a model, they can retrieve the relevant schema from their long term memory when attempting the task. Asking students to write a few specific sentences is a useful exercise.

Later lessons: Wider application

Once students have demonstrated the ability to accurately produce the construction in isolated drills, they could be asked to write a paragraph that contains noun appositives as one of the success criteria. Currently, I am teaching a year 9 class to write analytical essay introductions using noun appositives. They broadly followed a similar instructional sequence to the one above and, as a result, they have achieved a high success rate with this wider task. Later still, they could be asked to apply the constructions to more extended essay type answers.

General Principles

How long should you spend on each stage of the backwards fading continuum?

If we are to maximize efficiency in our instructional sequences-a key and important goal given that lesson time is finite-then we need to carefully consider two competing demands. Firstly, we should ensure that students have a high success rate: at least 70-80% for new material and even higher for material that is being practiced and firmed. Using worked examples and completion problems can make this level of success a reality, helping to minimize unwanted cognitive load. Secondly, we should use backwards fading so that students are asked to complete applications independently as quickly as possible. If we keep presenting worked examples, then not only will this waste time, but it may also prevent students from developing the ability to complete tasks without support. The example lessons above are an attempt to show how support should be faded, following the I-we-you continuum and ending with independent student application. How long students spend on each stage of the continuum is an empirical question and will largely be determined by the quality of examples (and non-examples) and completion problems that you use as well as the proficiency and prior knowledge of the students. Feedback to the teacher is key here: if students are performing successfully on a stage, then you can make the transition to a lower level of support, increasing the number of steps that a student is expected to complete.

How do you optimize practice drills?

Practice sentences should probably involve content from whatever it is you are studying as this will stretch and develop student thinking about the subject matter. Not only will students be developing their writing skills, but they will also be deepening their understanding of the content.

In Teach Like a Champion, Lemov explains ‘At Bats’, the idea that ‘succeeding once or twice at a skill won’t bring mastery, give your students lots and lots of practice mastering knowledge or skills’. This is crucial. When students are asked to complete problems independently, they should practice extensively, ideally across a number of lessons and including ‘multiple formats and with a significant number of plausible variations.’ Here are some of the possible variations when teaching appositives:

- Varying where the appositive is in a sentence (start, embedded or the end)

- Varying the writing genre for the task (analytical, descriptive, rhetorical)

- Varying the content (Macbeth, An Inspector Calls)

- Adding quotations to the appositive

- Varying the number of appositives in a sentence

- Varying the length and level of detail within the appositive: adding ‘who/that’ is a great way of adding further description

- When they have mastered all of the above, combining the appositive with other sentence skills that you are teaching

Engelmann’s track systems within his programs are fixed and have been created based upon rigorous field testing so as to ensure on optimum spacing, fading and efficiency. This requires a phenomenal amount of work and is almost certainly beyond the reach of busy teachers. At present we are not at a stage where these sequences have been formalized into our booklets, but this is slowly changing as we have developed progression models for both grammar and analytical skills, ensuring that we are consistent and that students master the skills of writing in a logical and methodical sequence.

Next Post: Further examples of backwards fading in English