Teaching students to write consistently well-structured essays is a vital part of our job as English teachers. Successful analytical writing will be made up of high quality components-precise vocabulary, sophisticated sentence structures, judicious use of evidence and perceptive interpretation-but the one thing that often signals truly exceptional performance is a level of crafting at the whole text level. The best analytical essays will be stuffed full of high quality components but, crucially, they will be organized in a logical and coherent way with a strong line of developing argument that threads through them. Not only that, but the writing will be pitched at a conceptual level, dealing with abstract notions and nominalized ideas. Instead of commenting on a hypocritical character, it will delve into the hypocrisy of an archetype; instead of exploring the unfair treatment of a girl, it will delve into the exploitation of the working class as a whole. Characters become constructs; language becomes symbolic and the tenor of the essay will be pitched far in excess of a mere analytical commentary where students move from quotation to quotation.

Exceptional essays do not begin with fine grained language analysis. Exceptional essays do not dive straight into the actions of a character. Exceptional essays begin with analytical introductions.

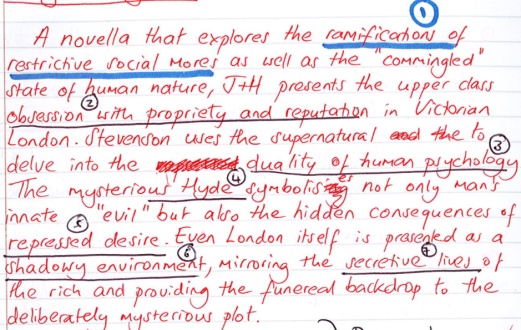

Here is an example:

Question: How does the novella explore the ideas of secrecy and the unknown?

Analytical Introductions will sketch out the big ideas within a text, often remaining at the level of the conceptual, the abstract and the thematic. They will often touch upon authorial intent and will contain a few succinct, well-chosen quotations to demonstrate that even at this level of abstraction, the interpretations are still based upon a close reading of the text. Appositive sentences lend themselves well to these introductions, allowing students to hit the examiner with thematic commentary from the very beginning.

Asking students to begin essays like this has a number of benefits. Firstly, it ensures that students are instantly writing about conceptual and thematic ideas, preventing them from slipping into the formulaic and prosaic repetition of PEEL paragraphs where a sequence of quotations are dissected and the word ‘connotations’ is lavishly slathered all over the writing as the true mark of critical interpretation. We’ve all read these essays before: they are repetitive and boring and the pages are filled with monotonous and relentless chains of language analysis. If students are to get top marks, they need to write in far more depth and with an appreciation of the big ideas that the text is commenting upon. Secondly, crafting an analytical introduction provides students with a plan. In the example above, each of the underlined words or phrases is not only a potential paragraph, but also the nascent beginnings of a topic sentence for that paragraph. Having the plan contained within the introduction can help students avoid getting carried away with one particular part of their essay. It can also help prevent students from frantically and randomly writing about stuff that they remember in a vain effort to fill the page with relevant content. Instead of students rushing to write about the first quote they remembered, followed by the next quote they remembered (from a different part of the text and about something entirely different), they will be led by the big ideas in the introduction. Thirdly, regular practice of these is a fantastic synoptic retrieval practice exercise.

Analytical introductions work equally well for exam questions with extracts and those without. If students are attempting a question with an extract, I will ask them to begin with the introduction, then deal with the extract, then revert back to the big ideas that they have touched upon in their introduction.

How to Teach Analytical Introductions?

We usually teach these in year 9 and they build upon The Six Skills. Although you can teach far simpler versions of these, for the example above, students would need to be secure in embedding evidence, writing appositives and using ‘not only…but’. Like many other things, initial teaching of these should span a minimum of two lessons with distributed practice spanning many more lessons. Initial lessons should involve the teacher writing and labelling a model, making their thought process explicit throughout by narrating WHY they have written it in the way that they have. In the first lesson, it can be useful to get kids to transform and rearrange a model into their own writing. This will inevitably involve a degree of mimicry but inflexible knowledge is almost always the start point in a sequence of learning.

Lesson 1 and 2

After writing the model, the teach underlines the big ideas, making it clear that these are the potential headings and inchoate topic sentences of conceptual paragraphs. The teacher then asks student to help them make a list of the ideas under the introduction. This list will be a paragraph plan and it is important to make this link clear to students as one of the functions of writing like this is to create a plan to follow. Asking students to use different words in the plan-essentially paraphrasing the introduction-is a useful check for understanding regarding vocabulary and the meaning of these conceptual phrases. The plan might look like this:

BIG IDEAS:

- Problems with super strict society

- Fixated on manners and how they behave

- We are all good and evil

- Hyde as a construct

- Denial of pleasure

- Gothic setting

- Paranoia/secrecy

Asking students to paraphrase the ideas also means that when you ask them to write their own, they are more likely to depart from the one above. Once they have compiled their list of big ideas, you can then ask them to reassemble this skeletal plan into an introduction of their own, perhaps changing the order in which they cover the themes and perhaps using different vocabulary or quotations. Before they being writing, it is worth reminding them of what they should not include:

- No language analysis

- No explanations, elaboration or justification

- No longer than the example

When they have finished writing their own, they can then label it in the same way that the teacher initially did and begin to think about which big idea should be dealt with first. Often, at this stage, it becomes apparent that the order that they appear in the introduction is not the most logical order for the essay. The order will sometimes be dictated by plot chronology; other times it will be because there is a natural link where one idea feeds into another: for instance, in the example above, there is a natural and obvious connection between paranoia/secrecy and problems with a super strict society as well as many other clear links.

Later Lessons

Example-problem pairs work particularly well with teaching this approach. A teacher could present an example like this:

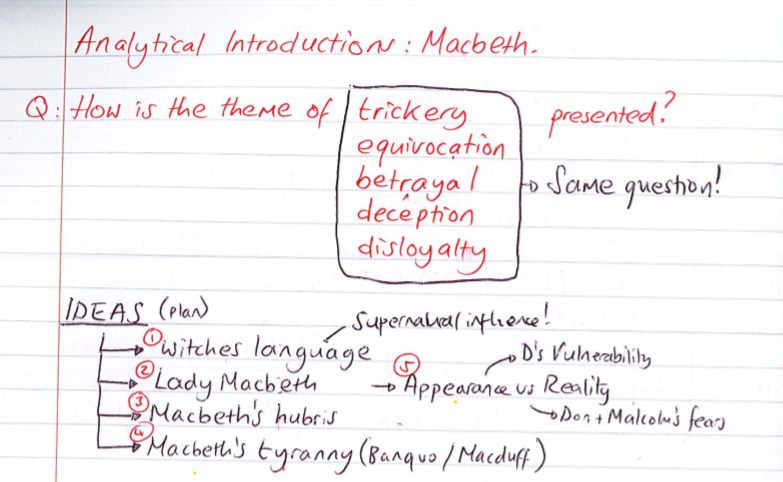

It can be really useful to group questions for students so that they begin to see the deep structure of what is being asked. Novices often fail to see similarities between questions, instead seeing a task as being unconnected to others. Demonstrating the similarity between tasks makes it far more likely that students will succeed: exam question words often confuse students and this approach can help to mitigate this problem.

The teacher could then ask students to generate the ideas-admittedly the example above could be improved by changing ‘Lady Macbeth’ to something more thematic and conceptual-perhaps manipulation or duplicity. This idea generation is a really useful synoptic retrieval task. The teacher can then write a model answer live:

Students can then be given a really similar question to attempt, allowing them to use this model as an analogy. The question will be different enough that they cannot just copy this model: this approach is something that is threaded throughout our booklets and is explained in this post

For students to really master this, it will need to be taught across multiple lessons and across the full range of texts that they are expected to respond to. An effective instructional sequence will probably move through the the six shifts of task design and will involve both the alternation strategy as well as backwards fading.

In the latter stages of examination preparation, giving students examination questions and asking them to create these at speed (once they have demonstrated an accurate and reasonably flexible understanding of them that is) can be a really useful way of practicing planning as well as being a useful synoptic retrieval task.

Next Post: Retrieval Practice 4: Extended Quizzing.