I have been teaching DI schemes for a couple of years now, having first been made aware of Engelmann’s work via Joe Kirby’s blog post https://pragmaticreform.wordpress.com/2013/02/02/direct-instruction/, which gives an excellent overview of the theory, approach and research base that supports it. The evidence base behind DI is wide ranging and robust: multiple large scale studies have been conducted over the past fifty years, demonstrating DI’s effectiveness. This recent article gives some links: https://edexcellence.net/articles/direct-instruction-the-rodney-dangerfield-of-curriculum. Kris Boulton has helpfully collated a number of resources and texts that explain the theory and evidence behind DI and you can find these here.

I teach Expressive Writing 2 and Corrective Reading B1 and B2; I have also set up a decoding intervention using Corrective Reading Decoding. Soon, I will be buying Spelling Through Morphographs in order to set up a spelling intervention.

Put simply, teaching these schemes and reading more about the theory behind DI has made me a more thoughtful and diligent teacher. While in the past, my approach to curriculum planning used to be the sum total of the number of lessons in a term, I now tackle it in a far more methodical and systematic way. This will be the first in a series of posts looking at what we can learn from Engelmann’s theory and approach.

While actual, published DI schemes take years to write, develop, test and refine, containing a daunting level of complexity, precision and detail, I will summarise some key ideas from Successful and Confident Students with Direct Instruction, a book that explains some general DI principles that can be applied to everyday teaching.

1) ‘A program design that supports mastery does not present great amounts of new information and skill training in each lesson. Rather, work is distributed so new parts in a lesson account for only 10-15 percent of the total lesson’ p.12

Only 15% of a lesson is new learning! 15%! 85% is spent practising, reviewing and recapping previous learning. Novices require extended practice and repeated exposure to new material if they are to truly master it. I would suggest that this percentage distribution is at best an exact inversion of how teaching is approached in many classrooms. Thinking of learning in terms of discrete, separate lessons combined with a fixation on variety, novelty and pace at all costs means that we may be making it hard for our students to master things. Quickly moving through content with no thought as to the necessity of recap and extended practice will almost always result in a lack of mastery and proficiency from students. Although I do not replicate this percentage distribution-my planning not being effective and efficient enough and the content being too wide to fit into the limited time that we have-since teaching DI schemes, I have massively increased the amount of practice and recap that I do.

2) ‘nothing is taught in one lesson. Instead, new concepts and skills are presented in two or three consecutive lessons to provide students with enough exposure to new material that they are able to use it in applications.’ p.12

If you present new information to students once, you can make a fairly safe bet that they will forget it. This is why retrieval practice is so important as it prevents forgetting. If we are going to ask students to complete ‘applications’ (in English this may be writing paragraphs or essays), then we need to ensure that they retain and are able to use the relevant pieces of knowledge (plot details, vocabulary, sentence constructions, analytical skills etc.) before doing so. A typical DI lesson will contain new material, material from the last few lessons that is ‘being firmed’ and material from earlier in the sequence which, because students have demonstrated sufficient proficiency and competency in restricted drills and practice exercises, is now being used in wider problem solving and freer applications. I wrote about how extended retrieval practice across different lessons can help students move from restricted recall to wider and freer application here. The post explores how to move students from inflexible to flexible knowledge, describing an approach that is heavily indebted to DI planning and sequences.

3) ‘The systematic stairway design does not provide relief because skills and knowledge do not go away. Once introduced, they are used throughout the rest of the program, either as elements that are used regularly (such as a word type that is learned), as details that are embedded in the problems and applications…or as items that are frequently reviewed’ p.14-15

Making choices as to the utility of what you teach is important: as mentioned in this post, choosing and teaching vocabulary that can be used across units and years means that the knowledge ‘will not go away’. Although it may be hard to plan for the usage and practice of a concept or skill across an entire unit or even curriculum, we should be trying as much as possible to do so. As mentioned here, we try to choose words to teach that have high utility-words that can be used across texts, units and school years.

4) ‘Most programs do not teach to mastery…Students will work on a particular unit for a few days and then it will be replaced by another unit that is not closely related to the first and that does not require application of the same skills and knowledge. This design, referred to as a “spiral curriculum”, is more comfortable for the program designers, teachers and students; however, it is inferior for teaching skills and knowledge’ p.16

Since teaching DI sequences, I am now hyperaware of the flaws and inadequacies of conventional medium and long term planning. The idea of a ‘spiral curriculum’ is common across subjects: in English it might mean ‘doing’ poetry once a year for five years in the hope that if they don’t get it the first time, there will be further opportunities to do so. While the spiral approach to curriculum planning is common place across subjects, Engelmann points out a number of flaws. Firstly, it creates a low expectation for performance as students are merely ‘exposed’ to content without any real expectation for mastery. Secondly, students quickly come to realise that the information and concepts that are being taught are temporary and will soon be replaced with another unit that ‘does not require application of skills and knowledge from the previous unit’. It is almost as if the spiral curriculum, by its very design and approach, reinforces apathy and a lack of application: if you knew that you would not need to use or be asked to use a concept again, then it might be entirely rational to give it less than the desired level of effort and thought. Disposable content fosters indifference.

The alternative to a spiral curriculum, and the approach favoured by Engelmann’s DI schemes, is called the strand curriculum. This paper provides a useful comparison between spiral and strand curricula, focussing on Maths.

In Expressive Writing, a DI corrective writing scheme that I teach which is aimed at helping students who write with poor grammar, bad punctuation and little coherence in their compositions, items are taught across multiple lessons and combined with other items to form a ‘strand curriculum’. In total, there are 55 carefully and methodically sequenced lessons. Exemplifying the premise that knowledge ‘does not go away’, the course teaches students to identify the parts of a sentence from lesson 1-10, then again intermittently from lessons 16-27. Capitals and full stops are taught from lesson 1-3, 11-14, and then intermittently from 16-55. All lessons end with a freer application (writing a story in this case) where students are required to apply ‘the same skills and knowledge’ from the drills and restricted practice activities earlier in the lesson and course.

Our English curriculum is deliberately narrow in terms of the types of texts that we ask students to write, focussing on ‘The Big Three’: analysis (responding to texts-a broad text type!); rhetoric (argument and persuasion) and descriptive/creative. The majority of student writing is focussed on analysis as the broad genre of responding to texts has the highest utility, applicable to all responses in literature and the reading responses in language. The finer details between different exam questions can be taught as exam technique in year 11: their core is broadly the same, sharing more similarities than differences. The three broad text types cover all literature and language questions, as well as hopefully providing a useful springboard for A-level and beyond. By narrowing our focus, we are able to go deeper and ensure that students hopefully master three, rather than being exposed to many and mastering none. Students know that subsequent units will ‘require application of the same skills and knowledge’. These ‘skills and knowledge’ are things like speech structure and rhetorical techniques for rhetoric; sentence structures for descriptive writing and our analytical approach (tentatively dubbed The 6 skills) for all forms of analysis and responding to texts, not to mention high-utility vocabulary that is applicable across units and texts. Our units deliberately attempt to intertwine all these aspects, containing elements from all three text types, deliberate sentence practice (see here for an overview), vocabulary and more. Although it is a million miles away from the level of rigour and complexity contained within DI schemes, it is an attempt to move beyond the flawed model of disposable, forgettable and separated units of unconnected lessons.

When choosing what items to teach, plan to teach them across multiple lessons, moving from a start point of restricted recall to an end point of freer application, as described in this post. We should also stop thinking of the ideal lesson as having one focus and one objective: instead, a lesson could have multiple foci: recalling, practising, ‘firming’ and applying items. As many others have pointed out, learning does not come in neat 60 minute chunks and our obsession with the lesson objective may not only be distorting our approach to curriculum planning, it may be actively lessening the efficacy of our teaching.

Next post: Insights from Direct Instruction part 2

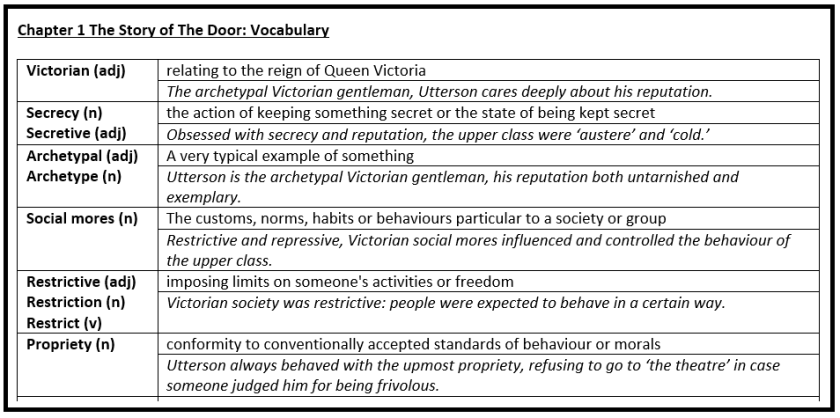

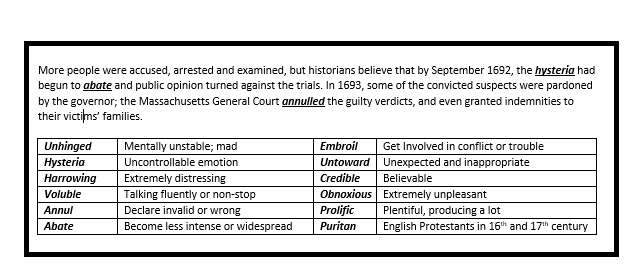

It is important to ensure that definitions are on the same page as the word that is being defined so students don’t have to flick back and forth in their booklets-an attempt to avoid falling foul of the split-attention effect (see Oliver Caviglioli’s brilliant visual summary of this aspect of Cognitive Load Theory

It is important to ensure that definitions are on the same page as the word that is being defined so students don’t have to flick back and forth in their booklets-an attempt to avoid falling foul of the split-attention effect (see Oliver Caviglioli’s brilliant visual summary of this aspect of Cognitive Load Theory